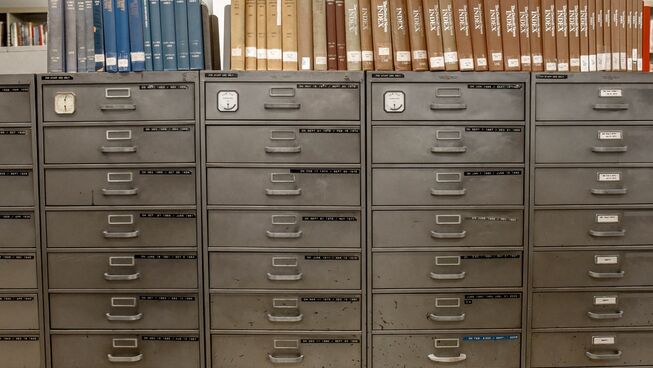

I once worked as a contractor on a software upgrade in a multi-departmental Victorian public service agency. The software package hadn't been upgraded in 13 years and was feeling its age, but my boss seemed excited to have me on the project and my colleagues were fantastic people.

After a few months of tender writing, interviewing staff across departments and mapping the company’s record management processes it became clear that even their 13-year-old system wasn’t really being used. HR staff printed, scanned, signed, re-scanned and emailed payslips every month, despite the bulk electronic signature feature circa 2003. Legal staff relied on printed documentation rather than electronic because of their fear of being audited. Engineering staff saved multiple copies of documents on hidden drives leading to errors, contract staff were sent on jobs with out-of-date plans. In some departments there was outright hostility towards me as a representative of higher management.

In Kafka’s The Castle, the protagonist K received a letter, appointing him as a Land Surveyor. When he first arrives in town near the Castle, he assumes his task will be straightforward, with the usual respect and cooperation that his training brings. Instead he found that even his title Land Surveyor was viewed with suspicion and that mysterious power structures prevented him from reaching the castle to begin work. If he questioned the nonsensical processes he encountered, they described them as “protocol”. (Kafka, 1926)

I devoured Kafka’s work when I was reflecting on my time in the public service, laughing bitterly, but I completely misunderstood its meaning at first.

I assumed the novel was saying that systems and processes make work futile, but in truth the message of The Castle is not to poke holes in modern bureaucracy but to critique systems that make us “outsiders” in our own workplaces.

What makes work futile in the Kafkaesque sense is not complex systems, but social and emotional distance. McCabe’s 2015 article articulated that the solution for inaccessible, complicated systems is not transparency, better organisation or a new framework, but systematising “empathy” (Mccabe, 2015, p. 1)

Have you ever felt a sense of insurmountable distance in your workplace? What do you think caused it? Was it the red-tape and processes? The working across states or international collaboration? Was it the time zone or the stressful merger with another department?

How can we cope with our sense of distance and futility at work?

A robust theology of work

The first answer to reducing our sense of futility is the realisation that God made us to work and that a biblical view of work expects difficulties. Genesis 3 shows us that Adam and Eve didn’t get much time in the garden before work became subject to a curse. We know futility was promised in the scriptures. Romans 8:20-21 says that the creation...

“...was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of Him who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself also will be set free from its slavery to corruption into the freedom of the glory of the children of God.”

In this way we know that futility at work is both normal and temporary.

Identifying and reducing alienation

If we recognise that our work frustration has a specific cultural or systematic cause, then we can actively take steps to reduce the “distance” which makes people miserable at work. We can build relationships with people, which will become more and more powerful as workplaces withdraw from the CBD and so many meetings are online.

We can also fight for workplaces to develop systems that show “empathy”. One of the most important fights in my role in the public service was for the recognition of a long term colleague’s work. My supervisor didn’t think it was significant, but I asked to be given time to prove that preserving their work was both soecially and economically beneficial, my supervisor accepted. So I rang around other similar organisations around Victoria and asked about the state of their documentation and how it affected their experience of upgrading, I asked internal staff what was really important to them in having an upgrade.

When the system consultants came to view our documentation they confirmed what I suspected, our files were the best they had seen in the business. The process was much smoother than expected because we retained order which reduced the angst associated with change. I like to think I reduced their sense of distance and hostility and affirmed the order bringing work of a long term staff member when I finished my contract.

What can you do to create a sense of meaning at work, for you and your colleagues?

It may just make yours, or someone else’s day.

Kafka, F. 1883-1924. (1926). The Castle. Schocken Books.

Mccabe, D. (2015). The Tyranny of Distance: Kafka and the problem of distance in bureaucratic organizations. Organization, 22(1), 58–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508413501936