Christmas: Fact or Fiction? dispelling the myths

Christmas is a joyous and fun occasion. Our guest for the most recently broadcast Bigger Questions, Mikey Bayliss, shares how he loves Christmas so much that he even sleeps under the Christmas tree!

Mikey has written an historical fiction book about Christmas: Journey from the East. He was inspired by English academic Sir Colin Humphreys who had a number of historical theories to explain some of the more unusual phenomena described in the biblical nativity accounts.

Mikey’s book is historical fiction - yet some would claim that the biblical Christmas story itself is also historical fiction.

So what are we to make of Christmas? Is the Christmas story based on fact or fiction?

How can you tell the difference between fact and fiction?

Mikey’s story is clearly historical fiction. Yet Christians claim that the Gospel stories are not fiction. Both are written in the style of a narrative, or story, so how do we tell the difference between a story designed to record fact and one meant to be historical fiction?

A crucial way of discerning the difference is through literary genre. Genre is crucial to a work’s interpretation.

Mikey’s book is written in the genre of a novel. When you pick it up and start reading it, one expects it to be fiction. Conversely the Gospels are written in the style of Greco-Roman biography. It was the biography of a recent character which was presumed to be historical.

Ancient readers would have expected the Gospels to be historical. This is clarified in the Prologue to Luke’s Gospel where he explicitly outlines his intention in writing is to record the ‘things fulfilled amongst us’.

“Gospels are ancient biography about a recent character for whom many sources remained; they are thus not analogous to collections of mythography or novels. Craig Keener

“If the early church had not been interested in the person and early life of Jesus, it would not have produced a Bioi with their narrative structure and chronological framework, but with discourses of the risen Christ like the ‘Gnostic Gospels’ instead (Richard Burridge, What are the Gospels? p.249).

The early church certainly understood the Gospels as historical and lived their lives on that assumption.

The magi included Kung Fu masters: fact or fiction?

Mikey’s book is an historical fiction built on the characters described in the nativity account from the Gospel of Matthew which mentions that Magi from the East came to Jerusalem to worship the one born king of the Jews (Matthew 2:1-2). So who were these Magi really?

Mikey’s book depicts them as a whole variety of people, including Kung Fu masters from China and Korea.

Whist it is plausible and tantalising that the Magi were from a variety of locations, including the far East. It is commonly believed that the Magi were astronomers from Mesopotamia, “the ancient home of the science-cum-superstition of ‘star gazing’” (Paul Barnett, Is the New Testament History?, p. 121).

Three wise men: fact or fiction?

Most Christmas pageants and the Christmas carol, We Three Kings, suggest that there were three Magi. By contrast, Mikey’s book proposes a whole entourage. Yet nowhere in the Gospels are just three Magi described. The number three derives from the number of gifts the Magi present, i.e. gold, incense and myrrh. Hence it is quite possible that there were a larger number of Magi than the gifts suggests (or possibly even just two!).

King Herod: fact or fiction?

King Herod was clearly an historical figure. He is very well attested in ancient history. Moreover the way Herod’s character is portrayed in the Gospels is consistent with the way that he is recorded elsewhere in ancient history, particularly the way he responds to the news of a newborn king by killing all the boys under two in the Bethlehem area. As Ancient Historian Paul Barnett says,

‘Herod’s paranoia in ordering the killing of the baby boys of Bethlehem is entirely in character. Earlier in his reign the king had murdered his wife Mariamne. More recently he removed two sons, prompting Augustus’ grim joke that it was safer to be Herod’s pig than Herod’s son… Later, knowing his own death was close, Herod ordered the arrest of the distinguished men from every village of Judaea and he ordered that the moment he expired they should be massacred. The order was not carried out. But the incident shows that the one who was capable of issuing it was also capable of ‘the slaughter of the innocents’ (Barnett, Is the New Testament History, p122-123).

The slaughter of the innocents: fact or fiction?

But did this slaughter really happen? This story is disputed because there is scant external historical records of the event. This event is specifically recorded only in Matthew 2:16,

16 When Herod realised that he had been outwitted by the Magi, he was furious, and he gave orders to kill all the boys in Bethlehem and its vicinity who were two years old and under, in accordance with the time he had learned from the Magi.

The main historian who documented much of this period of history, Josephus, is silent on such an event. So does this mean that this event is just a fiction?

The number of children killed in such a purge might only have been quite small. Bethlehem at the time was only a small town and some have estimated its population as low as just 300, meaning that only a small number of boys would have been killed.

The ancient world was a bloodthirsty place and many murders and killings would have gone unreported. The crucial question to establish is why an historian would be interested in recording such an event. Why would the murder of a few Jewish boys in a relatively small and unimportant town in a backwater in the Roman Empire pique the interest of other historians at the time?

Hence to demand that other historians must report a relatively minor act in the history of Israel and of Rome, overreaches on the expectations of historical reporting.

However, there is a potential reference to the event written by fourth century pagan author Macrobius who describes the reaction of Emperor Augustus to news from Palestine,

‘When he [Augustus] heard that Herod king of the Jews had ordered all the boys in Syria under the age of two years to be put to death and that the king’s son was among those killed, he said, ‘I’d rather be Herod’s pig than Herod’s son’.

Whilst it appears Macrobius has potentially garbled some events and locations, it is curious that he has mentioned a purge of boys under the age of two by King Herod.

The slaughter of the innocents may indeed be fact!

Contradictions in the biblical nativity accounts: does this mean they are fiction?

The Gospel of Matthew records the interaction with Herod and the Magi - yet the other account of the birth of Jesus in the Gospel of Luke - doesn’t record the Magi. It records the appearance of shepherds, which Matthew doesn’t record.

Leading critics of Christianity, like Richard Dawkins, and the late Christopher Hitchens see these contradictions and propose that the two accounts of the birth of Jesus contain glaring contradictions? Do these ‘glaring’ contradictions render the accounts as fabricated fiction?

Differences in accounts don’t automatically render them historically unreliable.

Many of the “contradictions” cited between Matthew and Luke are contradictions of silence, where where one historian records an event or detail another historian fails to record. These types of contradictions occur for several reasons:

(1) the historians utilise different sources, hence certain facts available to one are unavailable to the other.

(2) the historian deliberately supplements material already known to the readers from another source; hence one account will be silent.

(3) the historians may have different agendas, and hence emphasise and record certain events in greater detail and omit other details they deem less important to their purpose.

(4) economy of presentation may lead historians to omit historical details unnecessary to their purpose.

(5) the practice of paraphrase was a common feature of ancient histories where the ipsissima vox (actual voice) rather than the ipsissima verba (actual words) was utilised leading to variations and differences between accounts.

Within the infancy narratives, Matthew and Luke appear to operate independently by utilising different sources and hence may be unaware of the other details reported by the other author. They also have different agendas as Matthew intends to show a kingly Jesus being worshipped by foreign kings who is threatened by Herod, a prideful earthly king of the time. Whereas Luke desires to show more of the poverty and humility of Jesus, hence he writes about shepherds come to witness the one born and laid in a mean manger. Both authors have selected specific stories to support their presentations of Jesus fitting their agenda and purpose. They have excluded certain material, not because it didn’t happen, but because it didn’t fit their purpose.

Hence the differences between the infancy narratives does not automatically render them as fabrication.

Does the Christmas story take on more meaning or less if the events were fact rather than fiction?

According to Mikey, the Christmas story takes on far more meaning if it really did happen. If it didn’t happen, it’s a nice story, but doesn’t affect our lives today at all.

Yet, if it did happen, then the significance is enormous. It means that God has indeed come to dwell with us and brings hope, life and forgiveness.

The Christmas story: Fact or fiction?

The true Christmas message is life changing. It changed Mikey and it can change each one of us. There are good reasons to believe that the accounts in the Gospels record fact and not fiction.

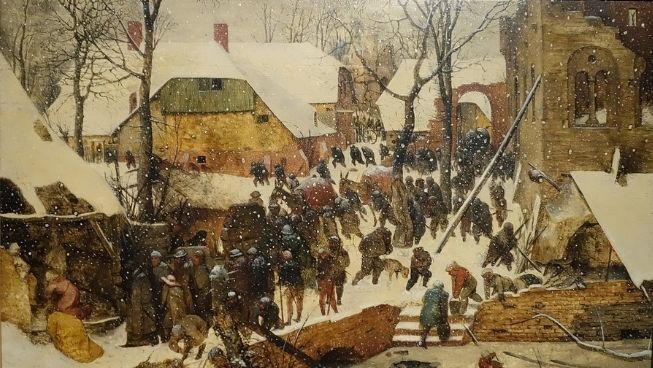

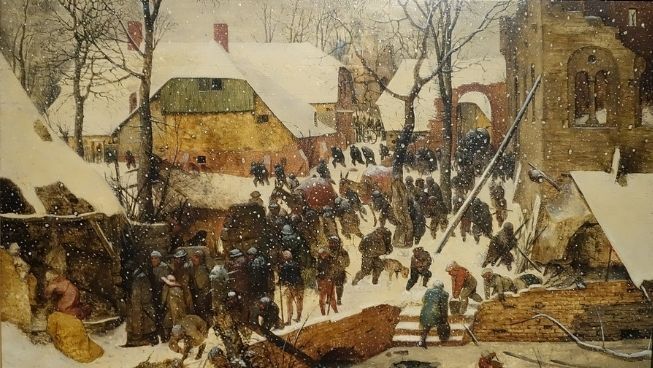

Follower of Hieronymus Bosch, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons